One of my Black Copper Marans hens flew up onto the roof of the coop today, which NONE of my flock members are in the habit of doing- that was Brutus’ job. I viewed it as a sign from the Little Guy as I prepared to write about the final chapter of his life.

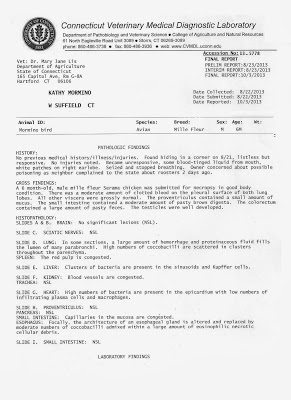

The leaves are changing here in New England, but the calendar on the final season of Brutus’ life remained unturned until this week. For those who may not have been following Brutus’ story, he was a 6 month old Mille Fleur Serama cockerel who died suddenly and unexpectedly on August 21st. His remains were submitted to the UCONN Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory for a necropsy, which is a post-mortem examination performed to determine the cause of death.

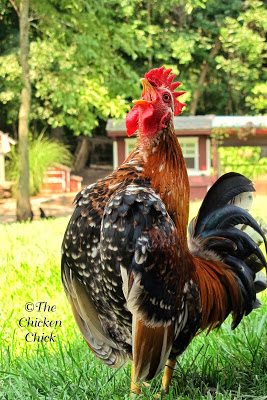

The preliminary necropsy report on August 23rd revealed that he died from a massive lung hemorrhage. Those results were shocking given that he was only 6 months old and in good health, exhibiting no sign of illness or injury until hours before his death. More tests were required to learn the cause of the hemorrhage. The following photo was taken the day before his passing.

At the time of the filing of the preliminary necropsy report, various tissues samples had not yet been analyzed and it has taken several months to determine the cause of death with specificity. The final necropsy report, issued yesterday, revealed that he died of septicemia, a bacterial blood infection. The poultry pathologist told me that there were lesions in his esophagus, which may have been caused by ingesting a foreign body (glass? a nail?) and it’s possible that was how the bacteria got into his bloodstream. She said this was just a theory as there was no foreign body found.

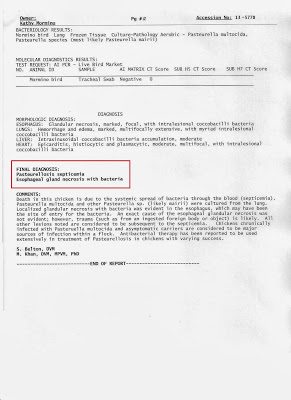

After receiving the report, I immediately consulted with Dr. Mike Petrik, DVM, MSc, The Chicken Vet for an interpretation of the report. I needed to know whether these findings have any implications for the rest of my flock. Dr. Petrik indicated that Brutus died from Pasterellosis, or fowl cholera, which is a highly contagious bacterial disease that can be spread by dogs, cats, beetles, rodents and other birds. He suggested that I obtain an “antibiotic sensitivity test” to find out which antibiotic this particular strain of Pasturella is vulnerable to.

I contacted the lab today to perform the sensitivity tests, which should be ready by Tuesday of next week. At that time, the entire flock will be treated with antibiotics for two weeks. The antibiotics will not eradicate the bacteria from the flock completely, but it will reduce the numbers and make it harder for it to return with a deadly vengeance.

According to Dr. Petrik, it is possible to vaccinate against fowl cholera, but the odds of a commercial vaccine matching up with the specific bacteria in my flock is slim. Much of the literature I have read recommends culling the entire flock. Culling is not an option for me in these circumstance any more than it was with my scissor-beaked hen, my pullet with prolapsed vent or chicks with spraddle leg. Most of the literature is geared toward recommendations for commercial poultry operations where the emphasis on egg production and risk management is entirely different from backyard flocks.

Brutus’ passing is sobering reminder of the importance of obtaining a necropsy when a bird dies from unknown causes. There is always the possibility that there are implications for the remaining flock members and the only way to protect them is to be armed with information obtained through a necropsy. I will treat my flock with the appropriate antibiotics for the proscribed course and continue caring for them in the same manner I always have. There is no way to insulate birds from every possible bacteria, virus, protozoa, germ, bug or cootie. The best any of us can do is to feed our flocks properly, ensure access to clean water and a clean living space, care for them when they’re ill to the best of our ability and not worry about the things that cannot be controlled.

Kathy Shea Mormino

Affectionately known internationally as The Chicken Chick®, Kathy Shea Mormino shares a fun-loving, informative style to raising backyard chickens. …Read on

shop my SPONSORS

One of my Black Copper Marans hens flew up onto the roof of the coop today, which NONE of my flock members are in the habit of doing- that was Brutus’ job. I viewed it as a sign from the Little Guy as I prepared to write about the final chapter of his life.

The leaves are changing here in New England, but the calendar on the final season of Brutus’ life remained unturned until this week. For those who may not have been following Brutus’ story, he was a 6 month old Mille Fleur Serama cockerel who died suddenly and unexpectedly on August 21st. His remains were submitted to the UCONN Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory for a necropsy, which is a post-mortem examination performed to determine the cause of death.

The preliminary necropsy report on August 23rd revealed that he died from a massive lung hemorrhage. Those results were shocking given that he was only 6 months old and in good health, exhibiting no sign of illness or injury until hours before his death. More tests were required to learn the cause of the hemorrhage. The following photo was taken the day before his passing.

At the time of the filing of the preliminary necropsy report, various tissues samples had not yet been analyzed and it has taken several months to determine the cause of death with specificity. The final necropsy report, issued yesterday, revealed that he died of septicemia, a bacterial blood infection. The poultry pathologist told me that there were lesions in his esophagus, which may have been caused by ingesting a foreign body (glass? a nail?) and it’s possible that was how the bacteria got into his bloodstream. She said this was just a theory as there was no foreign body found.

After receiving the report, I immediately consulted with Dr. Mike Petrik, DVM, MSc, The Chicken Vet for an interpretation of the report. I needed to know whether these findings have any implications for the rest of my flock. Dr. Petrik indicated that Brutus died from Pasterellosis, or fowl cholera, which is a highly contagious bacterial disease that can be spread by dogs, cats, beetles, rodents and other birds. He suggested that I obtain an “antibiotic sensitivity test” to find out which antibiotic this particular strain of Pasturella is vulnerable to.

I contacted the lab today to perform the sensitivity tests, which should be ready by Tuesday of next week. At that time, the entire flock will be treated with antibiotics for two weeks. The antibiotics will not eradicate the bacteria from the flock completely, but it will reduce the numbers and make it harder for it to return with a deadly vengeance.

According to Dr. Petrik, it is possible to vaccinate against fowl cholera, but the odds of a commercial vaccine matching up with the specific bacteria in my flock is slim. Much of the literature I have read recommends culling the entire flock. Culling is not an option for me in these circumstance any more than it was with my scissor-beaked hen, my pullet with prolapsed vent or chicks with spraddle leg. Most of the literature is geared toward recommendations for commercial poultry operations where the emphasis on egg production and risk management is entirely different from backyard flocks.

Brutus’ passing is sobering reminder of the importance of obtaining a necropsy when a bird dies from unknown causes. There is always the possibility that there are implications for the remaining flock members and the only way to protect them is to be armed with information obtained through a necropsy. I will treat my flock with the appropriate antibiotics for the proscribed course and continue caring for them in the same manner I always have. There is no way to insulate birds from every possible bacteria, virus, protozoa, germ, bug or cootie. The best any of us can do is to feed our flocks properly, ensure access to clean water and a clean living space, care for them when they’re ill to the best of our ability and not worry about the things that cannot be controlled.

You rock!I learn something new and useful with each and everyone of your postings!Thank you for all your info!

I follow already and definitely like the Facebook page. A waterer like this would be a great addition to my coop!

You are smart to treat the entire flock.

In 1973, I lost half my flock to Fowl Cholera. I didn't know any better and there was no way to get medical advice in those days. No chicken vets at all, no internet. It is so much better these days in that respect.

This waterer just might be my winter watering solution for my coop. Fingers crossed.

It saddens me to hear about your Brutus. He was a very handsome boy. I'm sure he is the top rooster in the big farmyard in the sky. He crows like my "Banchee" who I lost back in August to a tumor on his throat. I am lucky like you though, I also have video oh him crowing which I am grateful for.