It's late summer/early autumn and the floor of the coop looks like a pillow fight broke out overnight. Assuming the flock is healthy, older than 12 months, has no external parasites or other problems, they are most assuredly molting. Let's discuss what molting is, when it occurs and what can be done to help get chickens get through it efficiently.

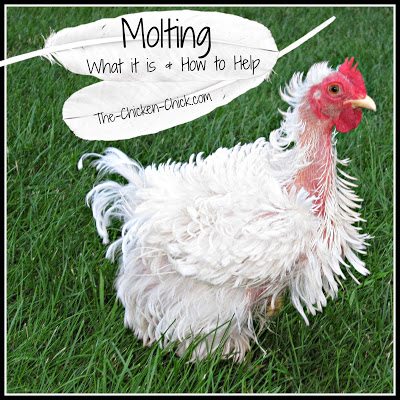

This is Phoebe, my bantam Frizzle Cochin in October 2010.

Molting is the natural shedding of old feathers and growth of new ones. Chickens molt in a predictable order beginning at the head and neck, proceeding down the back, breast, wings and tail. While molting occurs at fairly regular intervals for each chicken, it can occur at any time due to lack of water, food or sudden change in normal lighting conditions. Broody hens molt furiously after their eggs have hatched as they return to their normal eating and drinking routines.

FIRST JUVENILE MOLT

Chickens experience two, juvenile or "mini molts" as I like to call them, before a their first annual molt. The first mini molt begins at 6-8 days old and is complete by approximately 4 weeks when the chick's down is replaced by its first feathers.

SECOND JUVENILE MOLT

A chicken's second mini molt occurs between 7-12 weeks old when its first feathers are replaced by its second feathers. It is at this time that a rooster's distinguishing, ornamental feathers will appear.

ANNUAL MOLT

All chickens will molt annually, their first annual molt generally occurring around 16-18 months of age. During a molt, chickens will lose their feathers and grow new ones. Feathers consist of 85% protein and feather production places great demands on a chicken's energy and nutrient stores, as a result, egg production is likely to drop or stop entirely until the molt is finished. On average, molting takes 7-8 weeks from start to finish, but there is a wide range of normal from 4 to 12 weeks or more.

Both molting and egg production are controlled internally in response to lighting changes. When daylight hours decrease, egg production may slow down or stop completely and chickens will shed their feathers and grow new ones. When spring approaches and daytime lengthens, egg production will pick up again. At the end of summer, supplemental light may be added to the coop to promote egg-laying through the dark months.

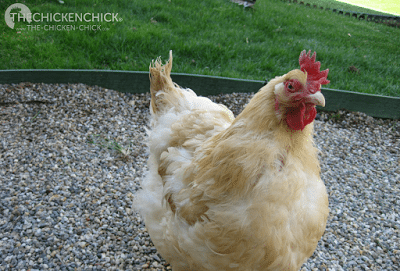

Lucy (Easter Egger)

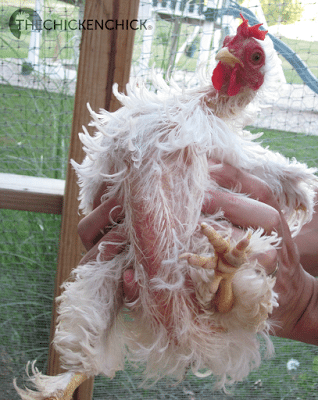

This is Phoebe, my White bantam frizzled Cochin, who is the poster chicken for a rough molt. She has molted in this most undignified manner for the past two years. She's a trooper though, I have yet to hear her demand a parka.

The tissue within the follicle of an emerging feather (aka: pin feather) contains a rich blood supply that will bleed if broken. Pin feathers are very sensitive and chickens generally prefer not to be handled while molting.

Feathers emerging through the vein-filled shaft, which is covered by a waxy coating (aka: the epitrichium).

An injured feather shaft is visible in this photo as a black spot of dried blood on top of the feather shaft.

Windy is a Blue Splash Marans hen who had injured one feather shaft, which bled profusely even though the injury was minor. A bird with a bleeding pin feather should be removed from the flock for treatment and their own safety. More on how to treat an injured chicken here.

If the bleeding will not stop, the pin feather should be removed with tweezers by grasping it at the base close to the skin and pulling quickly. Apply light pressure to the area until bleeding stops. Apply a little Vetericyn Wound & Infection spray or antibiotic ointment to the area and keep the bird apart from the flock until healed.

A waxy-type casing surrounds each new feather and either falls off or is removed by a preening chicken. The feather within then unfurls and the inner blood supply dries up (the feather shaft is then known as a quill).

HOW TO HELP CHICKENS GET THROUGH A MOLT & RETURN TO EGG LAYING

There are a few things that can be done to help chickens get through a molt a little bit easier:

- Reduce their stress level as much as possible. Try not to move them to a new living quarters or introduce any new flock members during a molt.

- Change their chicken feed to a higher protein feed such as an unmedicated starter, starter/grower or a grower feed for a couple of months until the majority of the flock is over the molting hump. This dietary change is preferable to injecting their diet with high protein foods that do not consist of the correct amino acids chickens require.

- Limit handling to avoid inflicting pain and to keep stress to a minimum.

**NO MORE THAN 5% of a hen's daily dietary intake should consist of anything other than their chicken feed.** No more than 2 tablespoons per bird on any given day and not every day. Oh, and good luck ensuring that Henrietta doesn't get more than her 2 tablespoons while Matilda gets none. That's how the pecking order works. Better to skip treats entirely as they are not beneficial.

EXCESS PROTEIN ADVISORY

Caution should be exercised when supplementing the chickens' diet with protein. Large amounts of protein can lead to diarrhea and other, serious problems.

"Excess protein in a chicken's diet is converted to uric acid and deposited as crystals in joints, causing gout. The excess use of meat scraps as a source of protein can also result in an imbalance of phosphorous."1

"Incorrect diets that contain excessive levels of protein causes wetter droppings since the extra protein is converted into urates. This causes your chicken to drink more therefore you will see an increase in urates leading to wet, damp bedding."2

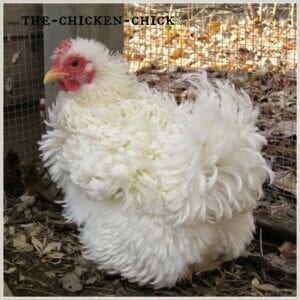

Remarkably, within a few weeks, dull and balding turns to shiny and voluminous.

Sources & further reading:

1 The Chicken Health Handbook, Damerow, Gail 1994 (pgs 27-28)

Mineral Deficiencies in Poultry

2 Treatment & Management of Diarrhoea

Kathy Shea Mormino

Affectionately known internationally as The Chicken Chick®, Kathy Shea Mormino shares a fun-loving, informative style to raising backyard chickens. …Read on

shop my SPONSORS

It's late summer/early autumn and the floor of the coop looks like a pillow fight broke out overnight. Assuming the flock is healthy, older than 12 months, has no external parasites or other problems, they are most assuredly molting. Let's discuss what molting is, when it occurs and what can be done to help get chickens get through it efficiently.

This is Phoebe, my bantam Frizzle Cochin in October 2010.

Molting is the natural shedding of old feathers and growth of new ones. Chickens molt in a predictable order beginning at the head and neck, proceeding down the back, breast, wings and tail. While molting occurs at fairly regular intervals for each chicken, it can occur at any time due to lack of water, food or sudden change in normal lighting conditions. Broody hens molt furiously after their eggs have hatched as they return to their normal eating and drinking routines.

FIRST JUVENILE MOLT

Chickens experience two, juvenile or "mini molts" as I like to call them, before a their first annual molt. The first mini molt begins at 6-8 days old and is complete by approximately 4 weeks when the chick's down is replaced by its first feathers.

SECOND JUVENILE MOLT

A chicken's second mini molt occurs between 7-12 weeks old when its first feathers are replaced by its second feathers. It is at this time that a rooster's distinguishing, ornamental feathers will appear.

ANNUAL MOLT

All chickens will molt annually, their first annual molt generally occurring around 16-18 months of age. During a molt, chickens will lose their feathers and grow new ones. Feathers consist of 85% protein and feather production places great demands on a chicken's energy and nutrient stores, as a result, egg production is likely to drop or stop entirely until the molt is finished. On average, molting takes 7-8 weeks from start to finish, but there is a wide range of normal from 4 to 12 weeks or more.

Both molting and egg production are controlled internally in response to lighting changes. When daylight hours decrease, egg production may slow down or stop completely and chickens will shed their feathers and grow new ones. When spring approaches and daytime lengthens, egg production will pick up again. At the end of summer, supplemental light may be added to the coop to promote egg-laying through the dark months.

Lucy (Easter Egger)

This is Phoebe, my White bantam frizzled Cochin, who is the poster chicken for a rough molt. She has molted in this most undignified manner for the past two years. She's a trooper though, I have yet to hear her demand a parka.

The tissue within the follicle of an emerging feather (aka: pin feather) contains a rich blood supply that will bleed if broken. Pin feathers are very sensitive and chickens generally prefer not to be handled while molting.

Feathers emerging through the vein-filled shaft, which is covered by a waxy coating (aka: the epitrichium).

An injured feather shaft is visible in this photo as a black spot of dried blood on top of the feather shaft.

Windy is a Blue Splash Marans hen who had injured one feather shaft, which bled profusely even though the injury was minor. A bird with a bleeding pin feather should be removed from the flock for treatment and their own safety. More on how to treat an injured chicken here.

If the bleeding will not stop, the pin feather should be removed with tweezers by grasping it at the base close to the skin and pulling quickly. Apply light pressure to the area until bleeding stops. Apply a little Vetericyn Wound & Infection spray or antibiotic ointment to the area and keep the bird apart from the flock until healed.

A waxy-type casing surrounds each new feather and either falls off or is removed by a preening chicken. The feather within then unfurls and the inner blood supply dries up (the feather shaft is then known as a quill).

HOW TO HELP CHICKENS GET THROUGH A MOLT & RETURN TO EGG LAYING

There are a few things that can be done to help chickens get through a molt a little bit easier:

- Reduce their stress level as much as possible. Try not to move them to a new living quarters or introduce any new flock members during a molt.

- Change their chicken feed to a higher protein feed such as an unmedicated starter, starter/grower or a grower feed for a couple of months until the majority of the flock is over the molting hump. This dietary change is preferable to injecting their diet with high protein foods that do not consist of the correct amino acids chickens require.

- Limit handling to avoid inflicting pain and to keep stress to a minimum.

**NO MORE THAN 5% of a hen's daily dietary intake should consist of anything other than their chicken feed.** No more than 2 tablespoons per bird on any given day and not every day. Oh, and good luck ensuring that Henrietta doesn't get more than her 2 tablespoons while Matilda gets none. That's how the pecking order works. Better to skip treats entirely as they are not beneficial.

EXCESS PROTEIN ADVISORY

Caution should be exercised when supplementing the chickens' diet with protein. Large amounts of protein can lead to diarrhea and other, serious problems.

"Excess protein in a chicken's diet is converted to uric acid and deposited as crystals in joints, causing gout. The excess use of meat scraps as a source of protein can also result in an imbalance of phosphorous."1

"Incorrect diets that contain excessive levels of protein causes wetter droppings since the extra protein is converted into urates. This causes your chicken to drink more therefore you will see an increase in urates leading to wet, damp bedding."2

Remarkably, within a few weeks, dull and balding turns to shiny and voluminous.

Sources & further reading:

1 The Chicken Health Handbook, Damerow, Gail 1994 (pgs 27-28)

Mineral Deficiencies in Poultry

2 Treatment & Management of Diarrhoea

Thank you for the information. Since I am new to chickens I will now know what to expect.

Thanks for the info,pictures always help with the understanding of chickens!

Great info, and my chickens just love the meal worm frenzy, they would be in heaven with all those treats!! :)

Great Photos

Spencer Knight

spencerknight12@yahoo.com

Great pictures for the topic! :)

Shellie

smw4211966@sbcglobal.net