Long before the Internet existed, people turned to renowned author, Gail Damerow’s books and articles for chicken care guidance. Enter the Internet and no shortage of questionable chicken care “advice” and discerning readers still flock to to the time-tested reliability of Gail Damerow’s writings for chicken care guidance. So, imagine my surprise to find an email from her in my inbox one day while writing my first book!

Since then, we have become fast friends and I am honored to be able to call her a mentor. I have to admit, it’s pretty nice to be able to pick up the phone to ask a question, to share ideas and collaborate on projects knowing there are few people on the planet as knowledgeable about chickens as she; and chickens aren’t her only subject of expertise!

A visit with Gail Damerow on her farm in Tennessee where she lives with her husband Allan

If you follow my Facebook page, you may know that I am embarking on an adventure in beekeeping. Don’t ask me how that happened as I have a healthy respect for and natural fear of stinging insects. But with the the assistance of my friends at Tractor Supply Company and generosity of the folks at Harvest Lane Honey, I am now a beekeeper! When I told Gail about this most unlikely turn of events, she shared a little bit about her adventures in beekeeping with me. I am beyond thrilled to present to you the first of an untold number of articles by, and collaborations with, the patron saint of poultry, Gail Damerow!

Gail Damerow with one of her Silkie hens

How Chickens and Honey Bees Are the Same, Only Different, by Gail Damerow

One day my husband Allan and I were cleaning out our chicken coop and I got to thinking about how so many back-to-landers have enthusiastically embraced both chickens and honey bees lately. Cleaning our sizable coop takes several hours, giving me a lot of time to wonder what chickens and bees have in common that makes them equally attractive to newbies.

Bees and chickens are both social creatures that prefer to live in groups, yet neither needs much by way of spacious housing. Even though a hive is home to many thousands of bees compared to a dozen or so chickens in a coop, the hive is much smaller and therefore easier to hide behind a fence or a few strategically placed bushes. Oh, sure, you can hide a chicken coop, too, but some hen always gives it away by cackling every time she lays an egg. And what does she have to boast about? After all, at best she lays only one egg a day. A queen bee busily lays a thousand or so eggs a day, leaving her little time to think about bragging. If she did holler after every egg, she’d have laryngitis in no time.

So why do we hide our hives and coops, anyway? Well, here’s where bees and chickens definitely have something in common. People who haven’t spent much time around either one know everything they need to know — that bees sting and chickens smell. Well, yeah. But cats scratch and dogs poop on sidewalks, yet I haven’t noticed any shortage of cats and dogs. Still, there’s always some neighborhood crank who’ll loudly proclaim opposition at the mere mention that you might be thinking of getting bees or chickens.

When you start out with either birds or bees, the first decision is what kind to get. Honey bees come in a few different races, chickens come in many different breeds. As with bees, some kinds of chickens are more excitable than others and some are more productive than others. Bees and chickens both come in a choice of black or designer stripes. But chickens have the edge here, because they come in many other colors, including red, white, and blue as well as in fancy-pants patterns like crele and porcelain.

Frizzled Tolbunt Polish, Calista Flockheart

Chickens and bees both attract predators, and some of the same predators, too. Skunks. Bears! Human ne’er-do-wells. Both are subject to theft, which serves to emphasize their respective desirability — at least among robbers who don’t worry the bees might sting or the chickens might smell. Bees and chickens both forage, but bees travel farther than chickens. Where a bee might look for nectar a couple of miles from the hive, the conservative chicken won’t travel much farther than a few hundred feet from the coop. Less, if no trees or shrubs offer protective cover.

Both bees and chickens need a steady supply of drinking water. If you don’t furnish it, they (bees and chickens alike) are apt to drown in some neighbor’s swimming pool. Both make sounds that reveal their status, if you take time to stop, look, and listen. With a flock of chickens, let out a whistle and they’ll stop whatever they’re doing and become quiet so you can hear coughs or sneezes. With bees, tap on the side of the hive and you will hear the bees buzz in response. A short buzz means all is well; a longer, sustained buzz means something’s going on — like your colony might be queenless — so you’d better check.

Birds and bees both fall prey to parasitic mites, although chicken mites are a heck of a lot easier to avoid and to treat than varroa mites. Both also attract beneficial scavenger mites that help keep their housing clean.

Speaking of clean, bees have the good sense to go outside to do their business. Chickens, on the other hand, don’t mind messing in their own house. And not just on the floor — on the walls and ceiling, too. How on earth do they do that? As big a chore as cleaning out all that chicken manure can be, it has the advantage that it may be composted and used in the garden to grow next summer’s vegetables. Bees, on the other hand, spread their wealth around where, I suppose, it does end up fertilizing something, unless it lands on your windshield.

Birds and bees both molt. A chicken molts four times before it reaches maturity. A bee molts six times, but gets all its molting done before it matures and doesn’t scatter feathers all over the place.

Both hatch in about three weeks —20 days for bees, 21 days for chicks. But the bee emerges as an adult, while the chick takes another four to five months to grow up. A queen bee mates a week or so after emerging and has all of three weeks during which to mate, otherwise she’ll lay infertile eggs that hatch into drones. A hen doesn’t start laying until she’s nearly five months old, and must mate about every two weeks to lay fertile eggs. If her eggs aren’t fertile, they won’t hatch. Period.

Hens and queen bees both lay decently well for a year or two before tapering off, which is why both are replaced by economy-minded keepers every year or so. If you get attached to your layers, you could easily end up running a old-fowl home for geriatric hens. With honey bees, however, if you don’t replace a negligent queen, the other bees will do it for you.

Bees have a much more complicated society and a stricter social structure than chickens. Each bee has a job and goes about it industriously for the betterment of the group. With chickens, it’s every hen for herself. Hens spend a lot of time in such self-indulgent activities as sunbathing, taking dirt baths, pecking tasty treats from the ground, and stealing tasty treats from other hens. You can spend a day in the chicken yard watching the activities of each individual chicken, but try spending a day keeping your eye on a single bee.

With a few hens, you’re likely to get daily rewarded with eggs. With a whole colony of bees, you don’t get rewarded with honey until the time is right, if at all. When you take a hen’s eggs, you don’t rob her of important nutrition and expect her to survive on something less healthy, like sugar water. On the other hand, some chicken keepers indulge their hens by feeding them corn or scratch grains — the chicken equivalent of junk food.

A colony of bees will rob honey from another colony. A flock of chickens won’t rob eggs from a neighboring flock, but a hen with maternal urges might increase the size of her brood by pilfering eggs (or even chicks) from another hen’s nest.

Both bees and chickens get confused when their house is moved. Move it more than a couple of feet and they will stubbornly fixate on the old location. Confining them inside for two or three days gives them time to reorient before you let them back out. For chickens, you keep the door shut. For bees, you stuff the entrance with grass or something similar; in the process of clearing out the stuffing, the bees reorient themselves.

If you summarily move their house, come nightfall chickens will go back to the old place and huddle in the dark. If it’s raining, they’ll huddle in a puddle. Bees are smarter. After circling the old place and finding the hive gone, they will circle in an ever widening spiral until they locate the hive by its odor — that is, unless the weather is cold, in which case bees, like chickens, may chill and die.

Regardless of the cause, if one chicken dies, up goes the red flag. But bees die routinely and constantly make replacements, so you’re unlikely to notice a serious problem until the problem gets serious. Chickens don’t mysteriously die in droves. Instead, they usually give you some advanced notice like coughing and sneezing or just hanging around looking perfectly miserable.

How chickens communicate is just as controversial a subject as how bees communicate. Some chicken keepers like to believe chicken sounds have abstract meanings, like the cackling hen is saying, “Woo-hoo! I laid another egg!” Others believe the cackle is just an instinctive survival mechanism through which the hen draws attention to herself, hoping any lurking predator will follow her and leave her defenseless egg alone. Similarly, some beekeepers believe the waggle dancing bee is saying, “Woo-hoo! I found some nifty new nectar!” and communicates such abstract information as the direction and distance of the nectar discovered. Others believe the dance is merely an instinctive survival mechanism that piques the curiosity of workers and sends them on their own odor search.

Much as a bee waggle dances to indicate a new food source, a hen utters the food call to show her chicks she’s found something yummy. A rooster uses the same food call to gather hens around himself, and then sometimes shows his true intent by segueing into a mating dance. If another rooster tries to horn in on the action, the two will duke it out until one gives up or is mortally wounded. Drones are much more civil. They congregate at a singles bar, waiting for a willing queen to swish through. The fastest Eddie gets the action, then dies happy and the next fastest takes over. No deceit and no squabbles.

A bee colony revolves around the queen. If more than one queen is present, either one queen kills the other or one queen leaves in a swarm. Hens live in groups and don’t swarm, unless someone left the gate open and they spot freshly sprouted seedlings or succulent ripening strawberries in the yard next door.

A flock of chickens revolves around the kingpin rooster. His functions (aside from fertilizing eggs) are to swagger around the yard, periodically crow to announce his presence, take full credit for every treat you bring your flock, and protect his hens from predators. Alas, most municipalities don’t allow roosters, which means a lot of today’s chicken keepers never have the pleasure of enjoying the antics of the hens’ better half. On the other hand, not all roosters are fun. Some roosters, and even an occasional hen, will attack its keeper. A mean rooster can stab repeatedly with his sharp spurs. A bee that stabs you with its sharp stinger dies. An attack rooster doesn’t die unless someone fetches the ax and transforms him into fricassee.

The clinical conditions of being afraid of bees and of chickens both start with an “A.” Apiphobia is a fear of bees. Alektorophobia is a fear of chickens. I’m afraid of bees, but not of chickens. As a kid I got stung plenty of times, but most likely not by honey bees. Try telling that to a little kid who hears something buzz and then gets a nasty sting. I hear a buzzing sound and right away the hairs raise on the back of my neck and I instinctively start swatting. I can’t help myself. Turns out, too, I’m allergic to bee stings (just as some unfortunate souls are allergic to chicken eggs).

When Allan decided to get honey bees I told him he’d have to take care of them himself. He elected me to keep the smoker going in case he needed it, which he rarely did. We both figured I’d be safe if I stayed far enough away and kept pumping the smoker. One day Allan was working his bees in the orchard when I wasn’t around to man the smoker. Suddenly one of his colonies boiled out of the hive and pursued him as he hotfooted the eighth mile to the house. That day I pulled 32 stingers out of his hide, but amazingly he suffered no ill effects. If that had been me, I’d be dead. Which is why we no longer have honey bees, but we still have chickens.

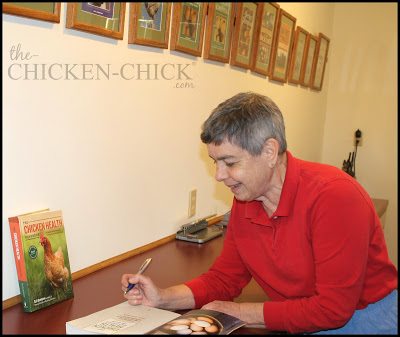

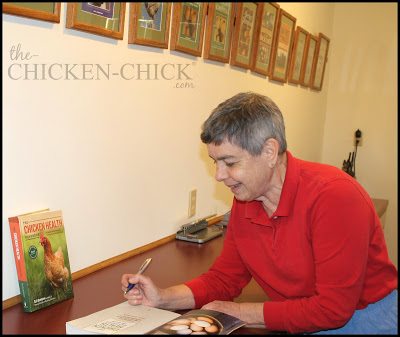

Gail Damerow is the author of The Chicken Health Handbook, Storey’s Guide to Raising Chickens, Hatching and Brooding Your Own Chicks, The Chicken Encyclopedia, The Backyard Homestead Guide to Raising Farm Animals and a flock of other books on poultry and related subjects.

Kathy Shea Mormino

Affectionately known internationally as The Chicken Chick®, Kathy Shea Mormino shares a fun-loving, informative style to raising backyard chickens. …Read on

shop my SPONSORS

Long before the Internet existed, people turned to renowned author, Gail Damerow’s books and articles for chicken care guidance. Enter the Internet and no shortage of questionable chicken care “advice” and discerning readers still flock to to the time-tested reliability of Gail Damerow’s writings for chicken care guidance. So, imagine my surprise to find an email from her in my inbox one day while writing my first book!

Since then, we have become fast friends and I am honored to be able to call her a mentor. I have to admit, it’s pretty nice to be able to pick up the phone to ask a question, to share ideas and collaborate on projects knowing there are few people on the planet as knowledgeable about chickens as she; and chickens aren’t her only subject of expertise!

A visit with Gail Damerow on her farm in Tennessee where she lives with her husband Allan

If you follow my Facebook page, you may know that I am embarking on an adventure in beekeeping. Don’t ask me how that happened as I have a healthy respect for and natural fear of stinging insects. But with the the assistance of my friends at Tractor Supply Company and generosity of the folks at Harvest Lane Honey, I am now a beekeeper! When I told Gail about this most unlikely turn of events, she shared a little bit about her adventures in beekeeping with me. I am beyond thrilled to present to you the first of an untold number of articles by, and collaborations with, the patron saint of poultry, Gail Damerow!

Gail Damerow with one of her Silkie hens

How Chickens and Honey Bees Are the Same, Only Different, by Gail Damerow

One day my husband Allan and I were cleaning out our chicken coop and I got to thinking about how so many back-to-landers have enthusiastically embraced both chickens and honey bees lately. Cleaning our sizable coop takes several hours, giving me a lot of time to wonder what chickens and bees have in common that makes them equally attractive to newbies.

Bees and chickens are both social creatures that prefer to live in groups, yet neither needs much by way of spacious housing. Even though a hive is home to many thousands of bees compared to a dozen or so chickens in a coop, the hive is much smaller and therefore easier to hide behind a fence or a few strategically placed bushes. Oh, sure, you can hide a chicken coop, too, but some hen always gives it away by cackling every time she lays an egg. And what does she have to boast about? After all, at best she lays only one egg a day. A queen bee busily lays a thousand or so eggs a day, leaving her little time to think about bragging. If she did holler after every egg, she’d have laryngitis in no time.

So why do we hide our hives and coops, anyway? Well, here’s where bees and chickens definitely have something in common. People who haven’t spent much time around either one know everything they need to know — that bees sting and chickens smell. Well, yeah. But cats scratch and dogs poop on sidewalks, yet I haven’t noticed any shortage of cats and dogs. Still, there’s always some neighborhood crank who’ll loudly proclaim opposition at the mere mention that you might be thinking of getting bees or chickens.

When you start out with either birds or bees, the first decision is what kind to get. Honey bees come in a few different races, chickens come in many different breeds. As with bees, some kinds of chickens are more excitable than others and some are more productive than others. Bees and chickens both come in a choice of black or designer stripes. But chickens have the edge here, because they come in many other colors, including red, white, and blue as well as in fancy-pants patterns like crele and porcelain.

Frizzled Tolbunt Polish, Calista Flockheart

Chickens and bees both attract predators, and some of the same predators, too. Skunks. Bears! Human ne’er-do-wells. Both are subject to theft, which serves to emphasize their respective desirability — at least among robbers who don’t worry the bees might sting or the chickens might smell. Bees and chickens both forage, but bees travel farther than chickens. Where a bee might look for nectar a couple of miles from the hive, the conservative chicken won’t travel much farther than a few hundred feet from the coop. Less, if no trees or shrubs offer protective cover.

Both bees and chickens need a steady supply of drinking water. If you don’t furnish it, they (bees and chickens alike) are apt to drown in some neighbor’s swimming pool. Both make sounds that reveal their status, if you take time to stop, look, and listen. With a flock of chickens, let out a whistle and they’ll stop whatever they’re doing and become quiet so you can hear coughs or sneezes. With bees, tap on the side of the hive and you will hear the bees buzz in response. A short buzz means all is well; a longer, sustained buzz means something’s going on — like your colony might be queenless — so you’d better check.

Birds and bees both fall prey to parasitic mites, although chicken mites are a heck of a lot easier to avoid and to treat than varroa mites. Both also attract beneficial scavenger mites that help keep their housing clean.

Speaking of clean, bees have the good sense to go outside to do their business. Chickens, on the other hand, don’t mind messing in their own house. And not just on the floor — on the walls and ceiling, too. How on earth do they do that? As big a chore as cleaning out all that chicken manure can be, it has the advantage that it may be composted and used in the garden to grow next summer’s vegetables. Bees, on the other hand, spread their wealth around where, I suppose, it does end up fertilizing something, unless it lands on your windshield.

Birds and bees both molt. A chicken molts four times before it reaches maturity. A bee molts six times, but gets all its molting done before it matures and doesn’t scatter feathers all over the place.

Both hatch in about three weeks —20 days for bees, 21 days for chicks. But the bee emerges as an adult, while the chick takes another four to five months to grow up. A queen bee mates a week or so after emerging and has all of three weeks during which to mate, otherwise she’ll lay infertile eggs that hatch into drones. A hen doesn’t start laying until she’s nearly five months old, and must mate about every two weeks to lay fertile eggs. If her eggs aren’t fertile, they won’t hatch. Period.

Hens and queen bees both lay decently well for a year or two before tapering off, which is why both are replaced by economy-minded keepers every year or so. If you get attached to your layers, you could easily end up running a old-fowl home for geriatric hens. With honey bees, however, if you don’t replace a negligent queen, the other bees will do it for you.

Bees have a much more complicated society and a stricter social structure than chickens. Each bee has a job and goes about it industriously for the betterment of the group. With chickens, it’s every hen for herself. Hens spend a lot of time in such self-indulgent activities as sunbathing, taking dirt baths, pecking tasty treats from the ground, and stealing tasty treats from other hens. You can spend a day in the chicken yard watching the activities of each individual chicken, but try spending a day keeping your eye on a single bee.

With a few hens, you’re likely to get daily rewarded with eggs. With a whole colony of bees, you don’t get rewarded with honey until the time is right, if at all. When you take a hen’s eggs, you don’t rob her of important nutrition and expect her to survive on something less healthy, like sugar water. On the other hand, some chicken keepers indulge their hens by feeding them corn or scratch grains — the chicken equivalent of junk food.

A colony of bees will rob honey from another colony. A flock of chickens won’t rob eggs from a neighboring flock, but a hen with maternal urges might increase the size of her brood by pilfering eggs (or even chicks) from another hen’s nest.

Both bees and chickens get confused when their house is moved. Move it more than a couple of feet and they will stubbornly fixate on the old location. Confining them inside for two or three days gives them time to reorient before you let them back out. For chickens, you keep the door shut. For bees, you stuff the entrance with grass or something similar; in the process of clearing out the stuffing, the bees reorient themselves.

If you summarily move their house, come nightfall chickens will go back to the old place and huddle in the dark. If it’s raining, they’ll huddle in a puddle. Bees are smarter. After circling the old place and finding the hive gone, they will circle in an ever widening spiral until they locate the hive by its odor — that is, unless the weather is cold, in which case bees, like chickens, may chill and die.

Regardless of the cause, if one chicken dies, up goes the red flag. But bees die routinely and constantly make replacements, so you’re unlikely to notice a serious problem until the problem gets serious. Chickens don’t mysteriously die in droves. Instead, they usually give you some advanced notice like coughing and sneezing or just hanging around looking perfectly miserable.

How chickens communicate is just as controversial a subject as how bees communicate. Some chicken keepers like to believe chicken sounds have abstract meanings, like the cackling hen is saying, “Woo-hoo! I laid another egg!” Others believe the cackle is just an instinctive survival mechanism through which the hen draws attention to herself, hoping any lurking predator will follow her and leave her defenseless egg alone. Similarly, some beekeepers believe the waggle dancing bee is saying, “Woo-hoo! I found some nifty new nectar!” and communicates such abstract information as the direction and distance of the nectar discovered. Others believe the dance is merely an instinctive survival mechanism that piques the curiosity of workers and sends them on their own odor search.

Much as a bee waggle dances to indicate a new food source, a hen utters the food call to show her chicks she’s found something yummy. A rooster uses the same food call to gather hens around himself, and then sometimes shows his true intent by segueing into a mating dance. If another rooster tries to horn in on the action, the two will duke it out until one gives up or is mortally wounded. Drones are much more civil. They congregate at a singles bar, waiting for a willing queen to swish through. The fastest Eddie gets the action, then dies happy and the next fastest takes over. No deceit and no squabbles.

A bee colony revolves around the queen. If more than one queen is present, either one queen kills the other or one queen leaves in a swarm. Hens live in groups and don’t swarm, unless someone left the gate open and they spot freshly sprouted seedlings or succulent ripening strawberries in the yard next door.

A flock of chickens revolves around the kingpin rooster. His functions (aside from fertilizing eggs) are to swagger around the yard, periodically crow to announce his presence, take full credit for every treat you bring your flock, and protect his hens from predators. Alas, most municipalities don’t allow roosters, which means a lot of today’s chicken keepers never have the pleasure of enjoying the antics of the hens’ better half. On the other hand, not all roosters are fun. Some roosters, and even an occasional hen, will attack its keeper. A mean rooster can stab repeatedly with his sharp spurs. A bee that stabs you with its sharp stinger dies. An attack rooster doesn’t die unless someone fetches the ax and transforms him into fricassee.

The clinical conditions of being afraid of bees and of chickens both start with an “A.” Apiphobia is a fear of bees. Alektorophobia is a fear of chickens. I’m afraid of bees, but not of chickens. As a kid I got stung plenty of times, but most likely not by honey bees. Try telling that to a little kid who hears something buzz and then gets a nasty sting. I hear a buzzing sound and right away the hairs raise on the back of my neck and I instinctively start swatting. I can’t help myself. Turns out, too, I’m allergic to bee stings (just as some unfortunate souls are allergic to chicken eggs).

When Allan decided to get honey bees I told him he’d have to take care of them himself. He elected me to keep the smoker going in case he needed it, which he rarely did. We both figured I’d be safe if I stayed far enough away and kept pumping the smoker. One day Allan was working his bees in the orchard when I wasn’t around to man the smoker. Suddenly one of his colonies boiled out of the hive and pursued him as he hotfooted the eighth mile to the house. That day I pulled 32 stingers out of his hide, but amazingly he suffered no ill effects. If that had been me, I’d be dead. Which is why we no longer have honey bees, but we still have chickens.

Gail Damerow is the author of The Chicken Health Handbook, Storey’s Guide to Raising Chickens, Hatching and Brooding Your Own Chicks, The Chicken Encyclopedia, The Backyard Homestead Guide to Raising Farm Animals and a flock of other books on poultry and related subjects.

Looking forward to reading your book this fall, Kathy! Yes, I still have my old, green Storey’s Guide to Raising Chickens by Gail Damerow, and have added her recent Chicken Health Handbook. I hope this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship between you two!

I’ve been wanting bees for some time. This was a great article. Thanks for sharing the info.

This spring we got our first bee hive and our first chickens! The chicks are only 2 weeks old and are growing like crazy!

I just ordered your book and Gail’s book, The Chicken Health Handbook. Thank you!

Great article—this is exactly where we are headed! We have been raising chickens for 3 years this April, and currently researching Beginner Beekeeping Kits. One of my sons has terrible allergies, and I would love to provide him with local honey, like from our own yard! Thank you for the info; you answered the questions I had running through my head :)