I consulted with board certified poultry veterinarians and a board certified veterinary pathologist while writing this article. While most of the treatment information below is regularly distributed by one of the vets to their patients, their legal department prefers no attribution. (Lawyers ruin all the fun.) I’ll take any information I can get for my chickens and yours from highly regarded and experienced poultry veterinarians though.

HOW DO CHICKENS GET WORMS?

Basically, chickens get worms from something they eat. Either a chicken eats infected droppings from another bird or the chicken eats an insect carrying worm eggs (earthworm, slug, snail, grasshopper, fly, etc). A healthy chicken can manage a reasonable worm load. When the chicken gets sick or otherwise stressed, their immune system is taxed and internal parasites have the opportunity to overpopulate. Worms inside a chicken aren’t aren’t always a problem, but when they are, they can cause disease, infection and death.

Slugs are an intermediate host, which means they carry one or more parasites that will infect a chicken only when the chicken eats the host.

WHAT KIND OF WORMS ARE WE TALKING ABOUT?

There are only a handful of worms that backyard chicken keepers need to concern themselves with ordinarily: capillary worms, cecal worms, gapeworms, roundworms and tapeworms. “There are several types of worms that cause infections, but few worms cause true disease in hens. (H)ens will often carry quite a load of worms before showing any signs.” Dr. Mike Petrik, DVM, MSc

Roundworms (Ascaridia galli):

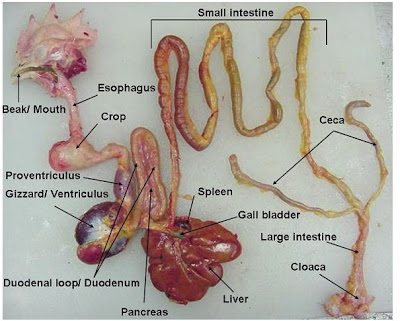

Roundworms are very common in backyard chickens. Heavy loads are visible in droppings, can be up to ~3″ long. Live in the small intestine & interfere with chicken’s ability to absorb nutrients; larvae damage the intestine walls, adults can create a blockage in the intestines, causing death. Roundworms cannot be transmitted from chickens to humans. The treatment of choice is piperazine.

Capillary Worms, aka: Hairworms, Threadworms (Capillaria):

Very thin, thread-like worms no more than .5″ long. Live in various body parts of chickens (crop, espohagus and intestines. Not ordinarily visible in droppings. Contracted through earthworms or picked up in litter. Can rob chickens of nutrients and vitamins.

Cecal worms (Heterakis gallinae):

Very common, not usually harmful to chickens. Live in ceca (2 branches off the intestine that end in 2 little pouches; the ceca are where the super stinky poop is made.). Visible with naked eye, ~.5″ long. Cecal worms are not ordinarily detrimental to chicken health. Cecal worms cannot be transmitted from chickens to humans. The cecal worm can be effectively treated with fenbendazole.

Gapeworms (Syngamus trachea):

Gapeworms are not very common in chickens. They live in the trachea, cause a chicken to open its mouth repeatedly, stretch its neck, gasp, cough or shake its head trying to dislodge the worms. Gapeworms have a red, fork-shaped appearance and are visible with naked eye. Transmitted by earthworms, slugs, flies and beetles. Require special treatment repeated over a period of 3 weeks. (Panacur, Ivermectin) Gapeworms cannot be transmitted from chickens to humans.

Tapeworms (Cestodes):

Tapeworms are common in chickens. Live in different areas of the intestines. Transmitted by beetles, earthworms, flies, slugs, etc. Require special treatment (Valbazen) and control of transmission sources. Difficult to treat, control transmission sources. Benzimidazoles, eg: fenbendazole or leviamisole, are the drugs of choice in treating chickens for tapeworms. Tapeworms cannot be transmitted from chickens to humans.

DETECTION

Symptoms of a worm infestation in chickens can include: worms in eggs, abnormal droppings, (diarrhea, foamy-looking, etc) weight loss, pale comb/wattles, listlessness, abnormal droppings, dirty vent feathers, worms in droppings or throat, gasping, head-stretching and shaking, reduced egg production and sudden death.

If birds are suspected of having a worm overload, a droppings sample should be brought to a veterinarian for a fecal float test. The vet can send the test directly to their lab for you. The test will reveal whether there is a problem, how serious it is and which type of worms are plaguing the bird.

It is important to understand that NOT all de-worming medications are capable of treating all types of worms.

WORM PREVENTION/CONTROL BEST PRACTICES

The best way to avoid having to concern yourself with a worm over-load is to keep the birds healthy; a healthy chicken can control a reasonable load of worms in its digestive tract.

- DO feed chickens properly. Limit treats to 5% of their daily diet, if any, and don’t add items to a quality commercial ration as doing so dilutes the carefully calculated nutrient balance in the feed.

- DON’T throw chicken feed or treats on the ground where it can become contaminated with infected droppings.

- DON’T overcrowd chickens in a coop or run.

- DO keep feeders clean.

- DO provide clean, fresh water daily and keep containers clean. Consider using a poultry nipple drinker.

- DO keep a clean, dry coop. Don’t allow droppings to accumulate. Use of a droppings board underneath roosts catches the night’s droppings, keeping litter cleaner, longer and provides an opportunity to observe abnormalities such as worms.

- DON’T keep water or food inside the coop!

- DO keep stress to a minimum. Stress taxes a chicken’s immune system, allowing worms to capitalize on the reduced resistance.

- DO provide flock with a sunny, dry yard.

- DO rotate pasture/pens/yards periodically, if possible. Chickens raised month after month on the same area at higher risk for contracting illness, disease and parasites than properly pastured birds given access to clean ground regularly.

- DO remove litter & replace periodically to break parasites’ life-cycles. (I use sand in my coops and runs, which creates an inhospitable environment to parasites. When properly maintained, it is not necessary to regularly replace.)

- DO contact your state Department of Agriculture Extension service poultry agent to discuss environmental specifics in your area and whether they lend themselves to a regular de-worming program and if so, what that should look like (contact information can be found HERE).

TREATMENT

Any time one chicken in a flock has a worm overload or is being treated for a suspected worm infestation, every member of the flock should be treated

According to Dr. Mike, The Chicken Vet, “The best strategy is to control worms twice per year: once in the fall, and once in the spring. To keep resistance from developing, you should rotate 2 or 3 of them in a program. Use product A in the fall, Product B in the spring, Product C in the following spring….etc.” Dr. Mike Petrik, DVM, MSc

Select one product that targets the type of worm plaguing your chickens and always treat the flock twice– once to paralyze and evict the adult parasites and again in 7-14 days (depending on the product) to eradicate the worms that have hatched from eggs since the first treatment. Clean the litter in the coop and run after the second treatment.

“You will see roundworms on the ground after deworming if they had a roundworm infestation. If you don’t see any, it doesn’t hurt the birds to de-worm anyway.” Dr. Michael Darre, MS, PhD, Poultry Professor, University of Connecticut

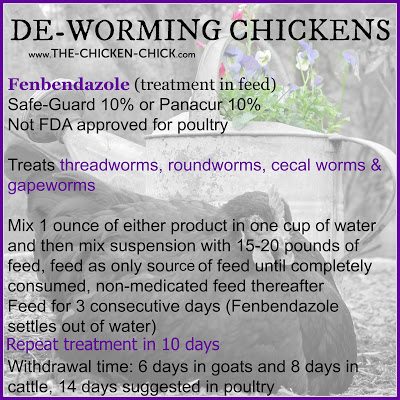

Safe-guard (fenbendazole) 10% treats threadworms, roundworms, cecal worms and gapeworms. Dosage for paste version: place a pea-sized dollop in beak or inside a piece of bread.

Repeat treatment in 10 days.

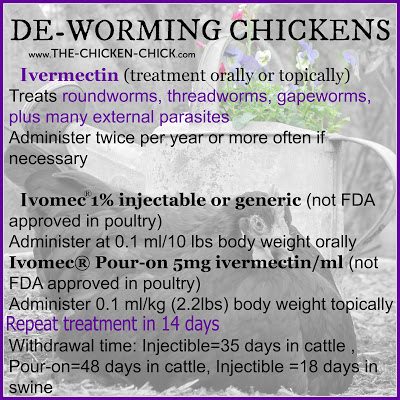

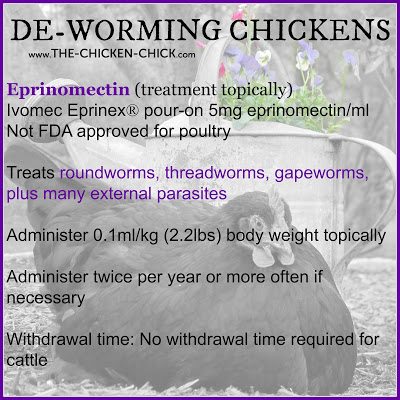

Ivermectin pour-on, applied to the back of chicken’s neck; 1 drop for tiny chickens, 3 drops for bantams, 4 for lightweight birds, 5 for large birds and 6 for heavy breeds.

Repeat treatment in 14 days. I do not recommend the use of Ivermectin unless under the supervision of a veterinarian. It is extremely easy to overdose and kill chickens with an incorrect dosage.

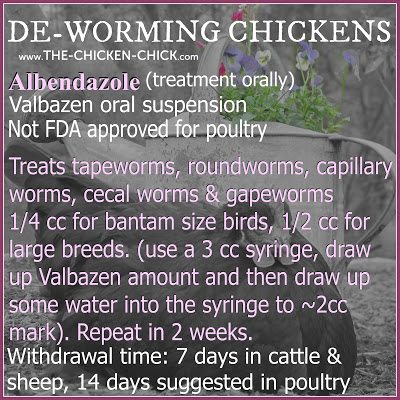

Valbazen Drench, treats tapeworms, roundworms, capillary worms, cecal worms & gapeworms. Oral dosages: 1/2 cc for large breeds, 1/4 cc for bantam sized birds. Use a 3cc syringe, draw up Valbazen dosage and then draw up some water into the syringe to approximately the 2cc mark for oral administration or soaked into bread and fed to birds individually.

Repeat treatment in 14 days.

ABOUT EGG WITHDRAWAL PERIODS

A withdrawal period is the minimum number of days that must pass from the time a chicken stops receiving a drug until the drug residue remaining in its body is reduced in its eggs or meat to an “acceptable level” to be safe for human consumption according to USDA standards. (paraphrased from The Chicken Encyclopedia) “If you cannot determine a specific drug’s withdrawal period, allow at least 30 days” before eating eggs or meat from a treated chicken.” Gail Damerow, The Chicken Encyclopedia

According to Dr. Petrick, The Chicken Vet, “Most worm medications have no [information about egg withdrawal periods] for laying hens. The reality is that most of the products are safe, and most don’t even get into the egg….they are medications that affect the gut and seldom are absorbed into the bloodstream. The problem is that there is no proof of their safety. Levamisole, fenbendazole (Safe-guard) and hygromycin are all effective anthelminthics (anti-worm drugs). To keep resistance from developing, you should rotate 2 or 3 of them in a program. Use product A in the fall, Product B in the spring, Product C in the following spring….etc.”

“Rooster Booster MultiWormer” is frequently used by folks hoping for a “more natural” de-wormer, however, what most do not realize is that it contains the antibiotic, Hygromycin B and it is not a treatment for a worm overload so much as a preventative to control the amount of worms in the digestive tract with continuous use. A 1.25 lb container costs upwards of ~$25 and must be fed to the flock every day for weeks to begin to control the population of only a few types of worms: capillary, cecal and roundworms. In practical terms, that adds $25 to every bag of chicken feed forever and will not begin working to reduce a worm overpopulation for many weeks in infested chickens.

A FEW WORDS ABOUT THE GREAT PUMPKIN CLAIM

According to Gail Damerow in The Chicken Health Handbook, 2 Ed.“Natural methods of worm control differ from chemical dewormers in not paralyzing or killing existing parasites but rather work by making the environment inside the chicken less attractive, or downright unpleasant, for parasites to take up residence. They are therefore more suited to preventing worms than to removing an existing worm load.”

There is NO scientific evidence anywhere suggesting that the active ingredient in pumpkin seeds (Curcurbitin) is capable of deworming or reducing worm loads in chickens. If I had roundworms in my digestive tract, I would not be willing to wage a bet that pumpkin seeds would eradicate the infestation in my gut, similarly, I am not willing to cause my chickens to suffer with a known worm overload while testing a theory with no evidence to support it.

Beware of the argument “I feed my chickens pumpkin seeds and they have never had worms therefore, pumpkin seeds are an effective, natural dewormer.” All backyard chickens carry some load of worms and healthy chickens can manage a normal worm load whether or not they eat pumpkins or pumpkin seeds. Read Much more on this topic here.

Any time a claim about pumpkins being a “natural de-wormer” is found, ask for specifics such as:

- Will the claimed effect be a complete de-worming of the chicken or merely a reduction in the number of worms in the chickens’ digestive tract?

- When will the claimed effect occur?

- Which of the five species of Cucurbita (pumpkins) should be used and which variety within the 9 cultivar groups should be used?

- What’s the needed percentage of Curcurbitin in the pumpkin seeds? How can the percentage be tested for?

- What quantity of pumpkin seeds should be fed per day per chicken?

- How often should the pumpkin seeds be fed to chickens to have the claimed effect?

Nobody has the answers to those questions. If they did, they’d be sitting on a beach in Hawaii, sipping a cold beverage paid for with the proceeds from the sales of the natural chicken de-worming product they patented and we all would be using it already.

Sources & Further Reading:

1 The Apha Practical Guide to Natural Medicines: The First Authoritative Home Reference For Herbs And Natural Remedies, Andrea Pierce, HarperCollins, 1999.

2 Dewormer Adjuncts, Control Without, or Along With, Chemicals, Karen Briggs with Craig Reinemeyer, DVM, PHD; Dennis French, DVM, MS, DIPL, ABVP; and Ray Kaplan, DVM, PHD. www.TheHorse.com, October 2004

Internal Parasites of Poultry

Internal Parasites

The Chicken Health Handbook

Poultry Production in Mississippi, Parasitic Diseases (internal)

Worming Treatments

Poultry Diseases & Medications for Small Flocks

Roundworms

The Chicken Encyclopedia

Gapeworms

The Chicken Health Handbook, 2edFDA, Piperazine

Benzimidazoles

Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture Study: DE

Overview of Helminthiasis in PoultryThe Informed Poultry Professional, University of Georgia

*Anatomical illustrations and photo reproduced for educational purposes, courtesy of Jacquie Jacob, Tony Pescatore and Austin Cantor, University of Kentucky College of Agriculture. Copyright 2011. Educational programs of Kentucky Cooperative Extension serve all people regardless of race, color, age, sex, religion, disability, or national origin. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, M. Scott Smith, Director, Land Grant Programs, University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Lexington,and Kentucky State University, Frankfort. Copyright 2011 for materials developed by University of Kentucky Cooperative Extension. This publication may be reproduced in portions or its entirety for educational and nonprofit purposes only. Permitted users shall give credit to the author(s) and include this copyright notice. Publications are also available on the World Wide Web at www.ca.uky.edu. Issued 02-2011

Kathy Shea Mormino

Affectionately known internationally as The Chicken Chick®, Kathy Shea Mormino shares a fun-loving, informative style to raising backyard chickens. …Read on

shop my SPONSORS

I consulted with board certified poultry veterinarians and a board certified veterinary pathologist while writing this article. While most of the treatment information below is regularly distributed by one of the vets to their patients, their legal department prefers no attribution. (Lawyers ruin all the fun.) I’ll take any information I can get for my chickens and yours from highly regarded and experienced poultry veterinarians though.

HOW DO CHICKENS GET WORMS?

Basically, chickens get worms from something they eat. Either a chicken eats infected droppings from another bird or the chicken eats an insect carrying worm eggs (earthworm, slug, snail, grasshopper, fly, etc). A healthy chicken can manage a reasonable worm load. When the chicken gets sick or otherwise stressed, their immune system is taxed and internal parasites have the opportunity to overpopulate. Worms inside a chicken aren’t aren’t always a problem, but when they are, they can cause disease, infection and death.

Slugs are an intermediate host, which means they carry one or more parasites that will infect a chicken only when the chicken eats the host.

WHAT KIND OF WORMS ARE WE TALKING ABOUT?

There are only a handful of worms that backyard chicken keepers need to concern themselves with ordinarily: capillary worms, cecal worms, gapeworms, roundworms and tapeworms. “There are several types of worms that cause infections, but few worms cause true disease in hens. (H)ens will often carry quite a load of worms before showing any signs.” Dr. Mike Petrik, DVM, MSc

Roundworms (Ascaridia galli):

Roundworms are very common in backyard chickens. Heavy loads are visible in droppings, can be up to ~3″ long. Live in the small intestine & interfere with chicken’s ability to absorb nutrients; larvae damage the intestine walls, adults can create a blockage in the intestines, causing death. Roundworms cannot be transmitted from chickens to humans. The treatment of choice is piperazine.

Capillary Worms, aka: Hairworms, Threadworms (Capillaria):

Very thin, thread-like worms no more than .5″ long. Live in various body parts of chickens (crop, espohagus and intestines. Not ordinarily visible in droppings. Contracted through earthworms or picked up in litter. Can rob chickens of nutrients and vitamins.

Cecal worms (Heterakis gallinae):

Very common, not usually harmful to chickens. Live in ceca (2 branches off the intestine that end in 2 little pouches; the ceca are where the super stinky poop is made.). Visible with naked eye, ~.5″ long. Cecal worms are not ordinarily detrimental to chicken health. Cecal worms cannot be transmitted from chickens to humans. The cecal worm can be effectively treated with fenbendazole.

Gapeworms (Syngamus trachea):

Gapeworms are not very common in chickens. They live in the trachea, cause a chicken to open its mouth repeatedly, stretch its neck, gasp, cough or shake its head trying to dislodge the worms. Gapeworms have a red, fork-shaped appearance and are visible with naked eye. Transmitted by earthworms, slugs, flies and beetles. Require special treatment repeated over a period of 3 weeks. (Panacur, Ivermectin) Gapeworms cannot be transmitted from chickens to humans.

Tapeworms (Cestodes):

Tapeworms are common in chickens. Live in different areas of the intestines. Transmitted by beetles, earthworms, flies, slugs, etc. Require special treatment (Valbazen) and control of transmission sources. Difficult to treat, control transmission sources. Benzimidazoles, eg: fenbendazole or leviamisole, are the drugs of choice in treating chickens for tapeworms. Tapeworms cannot be transmitted from chickens to humans.

DETECTION

Symptoms of a worm infestation in chickens can include: worms in eggs, abnormal droppings, (diarrhea, foamy-looking, etc) weight loss, pale comb/wattles, listlessness, abnormal droppings, dirty vent feathers, worms in droppings or throat, gasping, head-stretching and shaking, reduced egg production and sudden death.

If birds are suspected of having a worm overload, a droppings sample should be brought to a veterinarian for a fecal float test. The vet can send the test directly to their lab for you. The test will reveal whether there is a problem, how serious it is and which type of worms are plaguing the bird.

It is important to understand that NOT all de-worming medications are capable of treating all types of worms.

WORM PREVENTION/CONTROL BEST PRACTICES

The best way to avoid having to concern yourself with a worm over-load is to keep the birds healthy; a healthy chicken can control a reasonable load of worms in its digestive tract.

- DO feed chickens properly. Limit treats to 5% of their daily diet, if any, and don’t add items to a quality commercial ration as doing so dilutes the carefully calculated nutrient balance in the feed.

- DON’T throw chicken feed or treats on the ground where it can become contaminated with infected droppings.

- DON’T overcrowd chickens in a coop or run.

- DO keep feeders clean.

- DO provide clean, fresh water daily and keep containers clean. Consider using a poultry nipple drinker.

- DO keep a clean, dry coop. Don’t allow droppings to accumulate. Use of a droppings board underneath roosts catches the night’s droppings, keeping litter cleaner, longer and provides an opportunity to observe abnormalities such as worms.

- DON’T keep water or food inside the coop!

- DO keep stress to a minimum. Stress taxes a chicken’s immune system, allowing worms to capitalize on the reduced resistance.

- DO provide flock with a sunny, dry yard.

- DO rotate pasture/pens/yards periodically, if possible. Chickens raised month after month on the same area at higher risk for contracting illness, disease and parasites than properly pastured birds given access to clean ground regularly.

- DO remove litter & replace periodically to break parasites’ life-cycles. (I use sand in my coops and runs, which creates an inhospitable environment to parasites. When properly maintained, it is not necessary to regularly replace.)

- DO contact your state Department of Agriculture Extension service poultry agent to discuss environmental specifics in your area and whether they lend themselves to a regular de-worming program and if so, what that should look like (contact information can be found HERE).

TREATMENT

Any time one chicken in a flock has a worm overload or is being treated for a suspected worm infestation, every member of the flock should be treated

According to Dr. Mike, The Chicken Vet, “The best strategy is to control worms twice per year: once in the fall, and once in the spring. To keep resistance from developing, you should rotate 2 or 3 of them in a program. Use product A in the fall, Product B in the spring, Product C in the following spring….etc.” Dr. Mike Petrik, DVM, MSc

Select one product that targets the type of worm plaguing your chickens and always treat the flock twice– once to paralyze and evict the adult parasites and again in 7-14 days (depending on the product) to eradicate the worms that have hatched from eggs since the first treatment. Clean the litter in the coop and run after the second treatment.

“You will see roundworms on the ground after deworming if they had a roundworm infestation. If you don’t see any, it doesn’t hurt the birds to de-worm anyway.” Dr. Michael Darre, MS, PhD, Poultry Professor, University of Connecticut

Safe-guard (fenbendazole) 10% treats threadworms, roundworms, cecal worms and gapeworms. Dosage for paste version: place a pea-sized dollop in beak or inside a piece of bread.

Repeat treatment in 10 days.

Ivermectin pour-on, applied to the back of chicken’s neck; 1 drop for tiny chickens, 3 drops for bantams, 4 for lightweight birds, 5 for large birds and 6 for heavy breeds.

Repeat treatment in 14 days. I do not recommend the use of Ivermectin unless under the supervision of a veterinarian. It is extremely easy to overdose and kill chickens with an incorrect dosage.

Valbazen Drench, treats tapeworms, roundworms, capillary worms, cecal worms & gapeworms. Oral dosages: 1/2 cc for large breeds, 1/4 cc for bantam sized birds. Use a 3cc syringe, draw up Valbazen dosage and then draw up some water into the syringe to approximately the 2cc mark for oral administration or soaked into bread and fed to birds individually.

Repeat treatment in 14 days.

ABOUT EGG WITHDRAWAL PERIODS

A withdrawal period is the minimum number of days that must pass from the time a chicken stops receiving a drug until the drug residue remaining in its body is reduced in its eggs or meat to an “acceptable level” to be safe for human consumption according to USDA standards. (paraphrased from The Chicken Encyclopedia) “If you cannot determine a specific drug’s withdrawal period, allow at least 30 days” before eating eggs or meat from a treated chicken.” Gail Damerow, The Chicken Encyclopedia

According to Dr. Petrick, The Chicken Vet, “Most worm medications have no [information about egg withdrawal periods] for laying hens. The reality is that most of the products are safe, and most don’t even get into the egg….they are medications that affect the gut and seldom are absorbed into the bloodstream. The problem is that there is no proof of their safety. Levamisole, fenbendazole (Safe-guard) and hygromycin are all effective anthelminthics (anti-worm drugs). To keep resistance from developing, you should rotate 2 or 3 of them in a program. Use product A in the fall, Product B in the spring, Product C in the following spring….etc.”

“Rooster Booster MultiWormer” is frequently used by folks hoping for a “more natural” de-wormer, however, what most do not realize is that it contains the antibiotic, Hygromycin B and it is not a treatment for a worm overload so much as a preventative to control the amount of worms in the digestive tract with continuous use. A 1.25 lb container costs upwards of ~$25 and must be fed to the flock every day for weeks to begin to control the population of only a few types of worms: capillary, cecal and roundworms. In practical terms, that adds $25 to every bag of chicken feed forever and will not begin working to reduce a worm overpopulation for many weeks in infested chickens.

A FEW WORDS ABOUT THE GREAT PUMPKIN CLAIM

According to Gail Damerow in The Chicken Health Handbook, 2 Ed.“Natural methods of worm control differ from chemical dewormers in not paralyzing or killing existing parasites but rather work by making the environment inside the chicken less attractive, or downright unpleasant, for parasites to take up residence. They are therefore more suited to preventing worms than to removing an existing worm load.”

There is NO scientific evidence anywhere suggesting that the active ingredient in pumpkin seeds (Curcurbitin) is capable of deworming or reducing worm loads in chickens. If I had roundworms in my digestive tract, I would not be willing to wage a bet that pumpkin seeds would eradicate the infestation in my gut, similarly, I am not willing to cause my chickens to suffer with a known worm overload while testing a theory with no evidence to support it.

Beware of the argument “I feed my chickens pumpkin seeds and they have never had worms therefore, pumpkin seeds are an effective, natural dewormer.” All backyard chickens carry some load of worms and healthy chickens can manage a normal worm load whether or not they eat pumpkins or pumpkin seeds. Read Much more on this topic here.

Any time a claim about pumpkins being a “natural de-wormer” is found, ask for specifics such as:

- Will the claimed effect be a complete de-worming of the chicken or merely a reduction in the number of worms in the chickens’ digestive tract?

- When will the claimed effect occur?

- Which of the five species of Cucurbita (pumpkins) should be used and which variety within the 9 cultivar groups should be used?

- What’s the needed percentage of Curcurbitin in the pumpkin seeds? How can the percentage be tested for?

- What quantity of pumpkin seeds should be fed per day per chicken?

- How often should the pumpkin seeds be fed to chickens to have the claimed effect?

Nobody has the answers to those questions. If they did, they’d be sitting on a beach in Hawaii, sipping a cold beverage paid for with the proceeds from the sales of the natural chicken de-worming product they patented and we all would be using it already.

Sources & Further Reading:

1 The Apha Practical Guide to Natural Medicines: The First Authoritative Home Reference For Herbs And Natural Remedies, Andrea Pierce, HarperCollins, 1999.

2 Dewormer Adjuncts, Control Without, or Along With, Chemicals, Karen Briggs with Craig Reinemeyer, DVM, PHD; Dennis French, DVM, MS, DIPL, ABVP; and Ray Kaplan, DVM, PHD. www.TheHorse.com, October 2004

Internal Parasites of Poultry

Internal Parasites

The Chicken Health Handbook

Poultry Production in Mississippi, Parasitic Diseases (internal)

Worming Treatments

Poultry Diseases & Medications for Small Flocks

Roundworms

The Chicken Encyclopedia

Gapeworms

The Chicken Health Handbook, 2edFDA, Piperazine

Benzimidazoles

Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture Study: DE

Overview of Helminthiasis in PoultryThe Informed Poultry Professional, University of Georgia

*Anatomical illustrations and photo reproduced for educational purposes, courtesy of Jacquie Jacob, Tony Pescatore and Austin Cantor, University of Kentucky College of Agriculture. Copyright 2011. Educational programs of Kentucky Cooperative Extension serve all people regardless of race, color, age, sex, religion, disability, or national origin. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, M. Scott Smith, Director, Land Grant Programs, University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Lexington,and Kentucky State University, Frankfort. Copyright 2011 for materials developed by University of Kentucky Cooperative Extension. This publication may be reproduced in portions or its entirety for educational and nonprofit purposes only. Permitted users shall give credit to the author(s) and include this copyright notice. Publications are also available on the World Wide Web at www.ca.uky.edu. Issued 02-2011

Is it okay to worm when my hens are molting? Almost all my hens are in various stage of molt. Should I wait until they are finished molting?

You can. Whatever you feel comfortable with. There is always the option to test the worm load before beginning your de-worming program.

So, I’ve heard of a condition called “toxic worm die off”, which I guess can happen when you kill off a large infestation of worms, usually round worms, all at once and the chicken’s body is overwhelmed trying to eliminate the dead parasites and basically shuts down. I’ve avoided Wazine because of this, actually, as it only works on round worms. Is this a real thing? You interviewed several experts and it didn’t come up, so I’m wondering if I’ve misunderstood what I have read. I’d love to hear about this as we’re about to get a hard freeze and… Read more »

I have never heard of such a condition, however, I will say that if a chicken is so infested with worms that the treatment causes such a trauma to the body, the chicken keeper should have their birds confiscated. A worm infestation of that magnitude would be seen in droppings quite clearly.

What powder do you sprinkle on you poop boards after scraping? It looks like salt and I can not find the brand? Please help! Thank you

It’s Sweet Coop® Zeolite: http://amzn.to/2F6w5Tw

Great info!

My hen just got diagnosed with whipworms. How do I treat them?

Who made the diagnosis?