Yesterday I told you how my affilation with The Chicken Vet came about and today I have the privilege of introducing you to him formally. Dr. Mike Petrik is a doctor of veterinary medicine with a masters degree in animal welfare.

He graduated from the Ontario Veterinary College in 1998 and began working as a mixed large animal veterinarian until 2000 when he began working as a laying hen veterinarian, a position he has held ever since. In 2013, he graduated from the University of Guelph with his Master of Science degree in Animal Welfare. Dr. Petrik has worked on the scientific committee for both the Canadian meat bird and Canadian laying hens Codes of Practice, which are currently being updated.

He grew up on a professional poultry farm with laying hens, broiler chickens, turkeys and layer pullets where he gained an appreciation of the day-to-day care of the birds and an understanding of how things work, or don’t, in the real world. His family also raised pigs, beef cattle, and Standardbred race horses. In addition to his full time work as a poultry

veterinarian, he plays hockey, teaches SCUBA diving, plays guitar, runs in obstacle races and has “2 awesome kids” that take up the rest of his spare time.

Dr. Petrik has generously contributed to my blog over the past year-and-a-half on topics requiring a medical expert’s insight, ranging from vaccinations to worming, crop problems and the risks of diatomaceous earth. I am grateful for his generosity and contributions to the education of backyard chicken-keepers through my blog. Dr. Petrik also has a blog entitled “Mike, The Chicken Vet,” which I encourage you to follow for more of his witty and informative writings!

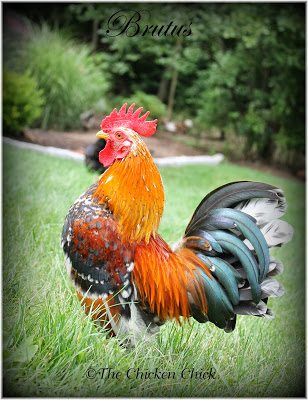

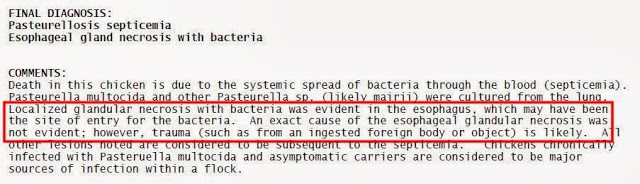

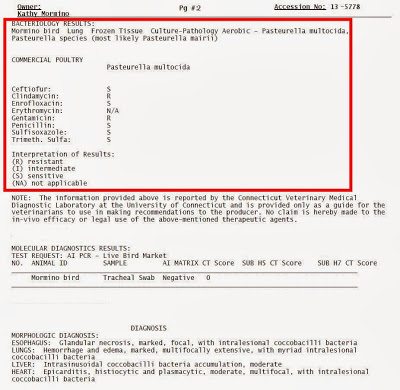

On a different note, when Brutus’ necropsy report came back with Pasturella/poultry cholera as the cause of death, it raised more questions about the implications of bacterial infection for my flock and backyard flocks in general, so I turned to Dr. Petrick for insight on bacterial infections in backyard flocks. The following is his reply…

When Kathy asked me to write a segment on bacterial infections and chickens, I was overwhelmed. I have books I have trouble lifting on the subject. I couldn’t decide how to approach such a wide, deep, complicated and important topic to make any real sense of it. So, I decided to talk to my 7 year old. I have found that if I can make her understand what I am saying, I am hitting the important parts….she is also very smart, and really makes me stretch sometimes to find answers for her. Here goes…

First of all, it is crucial to realize that bacteria are EVERYWHERE, and your flock has loads of them. I guarantee that I can come to any flock in the world and find potentially devastating bacteria…..professional, backyard, it doesn’t matter. Every flock is exposed to, and at risk of bacterial infection all the time. Instead of wondering why flocks get sick, I often wonder how any flocks are healthy!

Maxim #1: Poison is in the dose.

Too much water will kill you (no, not drowning, but if you drink too much water, it will destroy your kidneys). So will too much salt. The jury is out on hot sauce, but I’ll get back to you on it. The point is, a very few bad bacteria won’t make your flock sick, and a tidal wave of normally benign bacteria will make the flock desperately ill. Control the amount of bacteria your hens are exposed to by keeping the coop and yard clean, remove standing water (ideal place for bacterial “blooms”) and be careful when you expose your hens to other flocks, even if you do it accidentally by visiting other chickens and not changing your shoes before you visit your own flock.

Maxim #2: Stress cripples the immune system

Fight or flight reactions divert body resources from long term survival processes (digestion, reproduction, immune function) to short term survival processes (increased blood supply to muscles, increased heart rate, wild and creepy look in her eye). The problem is, there is a pretty much constant war going on in the hen’s body between the immune system and the bacteria that surround her. If you cripple the immune system, the bacteria get a leg up, and a situation that would normally not result in sickness can become dangerous, especially if the stress is longer term, such a cold weather, introduction of new members of the flock, constant harassment by a predator outside the coop.

Maxim #3: You will never get rid of an infection

Because bacteria occur in such huge numbers, it is all but impossible to completely rid a flock of them. A dentistry site estimates 20 billion microbes (bacteria) live in a healthy mouth. Even if we had you gargle with Lysol (you know, kills 99.9% of bacteria), you would still have 20, 000, 000 bacteria in your mouth….consider that the next time your 2 year old wants to plant a wet one on you. The really bad news is that when you have a bacterial infection, the numbers will go up substantially. The good news is that hens (and us) have the ability to ramp up our defenses to get rid of even these massive numbers of bacteria (exception, see Maxim #2).

Maxim #4: There are ALWAYS resistant bacteria

Because of the massive number of bacteria present in an infection, there is a fair amount of variability in their metabolism. If you treat with anything… an antibiotic, vinegar, Lysol….some of them will not be affected. These bacteria will then attempt to expand into the area where the other bacteria used to live before you killed them….except all the ones that now live there will have grown from bacteria that the agent couldn’t kill. This is how antibiotic resistance develops. The unfortunate thing is that, as you select for tougher bacteria, they are more and more difficult to kill, even if you use another agent, and become more pathogenic (ie they become tougher for the animal to fight off as well).

With these maxims in mind, your approach to bacterial infections should start with:

1) Isolate sick hens from healthy ones

The greatest source of bacteria for healthy hens is a nearby sick hen. The bacteria that have made one sick have already proven that they are pathogenic and capable of causing disease. Reduce the risk of the disease spreading.

2) Try to find how the bacteria got past the first line of defense of the bird.

Her skin, nasal passages and GI tract are very specialized in keeping out bacteria….there

is a reason they failed, and if you can discover it, it will go a long way to helping treat her and prevent further infections.

3) Try to identify the bacterial culprit.

Hens try to fight off all bacteria in similar ways….they get a fever, they produce a cheesy form of pus around the infection, and try to protect the area. If the infection is in the lung, or internal, you might not see the pus, but only notice that the hen isn’t doing well. Try to identify if it is a gut, respiratory, reproductive or skin infection, and get the bug identified through culture at a vetclinic. Sometimes you can take swabs yourself if you can work with your vet to get appropriate swabs to use. Treating blindly is sometimes all that is available to us, but if you have a chance to swab the area, your treatment will be MUCH more likely to work.

4) Get an antibiotic sensitivity test done to find what type of antibiotic works best for that bacteria.

Treating E. coli with penicillin not only will not work, it will create a whole bunch of penicillin resistant bacteria elsewhere in the body, that may become a problem later. Treat aggressively to knock back the bacterial load, and nurse the patient as best you can by keeping her warm and hydrated. Remember…..all antibiotics will do is knock back the

numbers a bit so that the hen can win the war…..if she can’t fight, your antibiotic treatment will NEVER clear the infection.

5) Use antibiotics sparingly

The more you use them, the less well they will work in the future because there will be a more resistant population of bugs around your flock due to previous treatments.

6) Do your best to clean the areas the sick birds were in contact with.

Talk to your vet and find out which bacteria like to live in the soil, or in the water, or wherever, and do your best to reduce the numbers there.

This only scratches the surface of how bacteria behave and how chickens and bacteria interact, but it will give you some basic outlines to help reduce the bacterial load in your hens.

Hope that helps!

Dr. Mike Petrik, DVM, MSc

Mike, The Chicken Vet

Kathy Shea Mormino

Affectionately known internationally as The Chicken Chick®, Kathy Shea Mormino shares a fun-loving, informative style to raising backyard chickens. …Read on

shop my SPONSORS

Yesterday I told you how my affilation with The Chicken Vet came about and today I have the privilege of introducing you to him formally. Dr. Mike Petrik is a doctor of veterinary medicine with a masters degree in animal welfare.

He graduated from the Ontario Veterinary College in 1998 and began working as a mixed large animal veterinarian until 2000 when he began working as a laying hen veterinarian, a position he has held ever since. In 2013, he graduated from the University of Guelph with his Master of Science degree in Animal Welfare. Dr. Petrik has worked on the scientific committee for both the Canadian meat bird and Canadian laying hens Codes of Practice, which are currently being updated.

He grew up on a professional poultry farm with laying hens, broiler chickens, turkeys and layer pullets where he gained an appreciation of the day-to-day care of the birds and an understanding of how things work, or don’t, in the real world. His family also raised pigs, beef cattle, and Standardbred race horses. In addition to his full time work as a poultry

veterinarian, he plays hockey, teaches SCUBA diving, plays guitar, runs in obstacle races and has “2 awesome kids” that take up the rest of his spare time.

Dr. Petrik has generously contributed to my blog over the past year-and-a-half on topics requiring a medical expert’s insight, ranging from vaccinations to worming, crop problems and the risks of diatomaceous earth. I am grateful for his generosity and contributions to the education of backyard chicken-keepers through my blog. Dr. Petrik also has a blog entitled “Mike, The Chicken Vet,” which I encourage you to follow for more of his witty and informative writings!

On a different note, when Brutus’ necropsy report came back with Pasturella/poultry cholera as the cause of death, it raised more questions about the implications of bacterial infection for my flock and backyard flocks in general, so I turned to Dr. Petrick for insight on bacterial infections in backyard flocks. The following is his reply…

When Kathy asked me to write a segment on bacterial infections and chickens, I was overwhelmed. I have books I have trouble lifting on the subject. I couldn’t decide how to approach such a wide, deep, complicated and important topic to make any real sense of it. So, I decided to talk to my 7 year old. I have found that if I can make her understand what I am saying, I am hitting the important parts….she is also very smart, and really makes me stretch sometimes to find answers for her. Here goes…

First of all, it is crucial to realize that bacteria are EVERYWHERE, and your flock has loads of them. I guarantee that I can come to any flock in the world and find potentially devastating bacteria…..professional, backyard, it doesn’t matter. Every flock is exposed to, and at risk of bacterial infection all the time. Instead of wondering why flocks get sick, I often wonder how any flocks are healthy!

Maxim #1: Poison is in the dose.

Too much water will kill you (no, not drowning, but if you drink too much water, it will destroy your kidneys). So will too much salt. The jury is out on hot sauce, but I’ll get back to you on it. The point is, a very few bad bacteria won’t make your flock sick, and a tidal wave of normally benign bacteria will make the flock desperately ill. Control the amount of bacteria your hens are exposed to by keeping the coop and yard clean, remove standing water (ideal place for bacterial “blooms”) and be careful when you expose your hens to other flocks, even if you do it accidentally by visiting other chickens and not changing your shoes before you visit your own flock.

Maxim #2: Stress cripples the immune system

Fight or flight reactions divert body resources from long term survival processes (digestion, reproduction, immune function) to short term survival processes (increased blood supply to muscles, increased heart rate, wild and creepy look in her eye). The problem is, there is a pretty much constant war going on in the hen’s body between the immune system and the bacteria that surround her. If you cripple the immune system, the bacteria get a leg up, and a situation that would normally not result in sickness can become dangerous, especially if the stress is longer term, such a cold weather, introduction of new members of the flock, constant harassment by a predator outside the coop.

Maxim #3: You will never get rid of an infection

Because bacteria occur in such huge numbers, it is all but impossible to completely rid a flock of them. A dentistry site estimates 20 billion microbes (bacteria) live in a healthy mouth. Even if we had you gargle with Lysol (you know, kills 99.9% of bacteria), you would still have 20, 000, 000 bacteria in your mouth….consider that the next time your 2 year old wants to plant a wet one on you. The really bad news is that when you have a bacterial infection, the numbers will go up substantially. The good news is that hens (and us) have the ability to ramp up our defenses to get rid of even these massive numbers of bacteria (exception, see Maxim #2).

Maxim #4: There are ALWAYS resistant bacteria

Because of the massive number of bacteria present in an infection, there is a fair amount of variability in their metabolism. If you treat with anything… an antibiotic, vinegar, Lysol….some of them will not be affected. These bacteria will then attempt to expand into the area where the other bacteria used to live before you killed them….except all the ones that now live there will have grown from bacteria that the agent couldn’t kill. This is how antibiotic resistance develops. The unfortunate thing is that, as you select for tougher bacteria, they are more and more difficult to kill, even if you use another agent, and become more pathogenic (ie they become tougher for the animal to fight off as well).

With these maxims in mind, your approach to bacterial infections should start with:

1) Isolate sick hens from healthy ones

The greatest source of bacteria for healthy hens is a nearby sick hen. The bacteria that have made one sick have already proven that they are pathogenic and capable of causing disease. Reduce the risk of the disease spreading.

2) Try to find how the bacteria got past the first line of defense of the bird.

Her skin, nasal passages and GI tract are very specialized in keeping out bacteria….there

is a reason they failed, and if you can discover it, it will go a long way to helping treat her and prevent further infections.

3) Try to identify the bacterial culprit.

Hens try to fight off all bacteria in similar ways….they get a fever, they produce a cheesy form of pus around the infection, and try to protect the area. If the infection is in the lung, or internal, you might not see the pus, but only notice that the hen isn’t doing well. Try to identify if it is a gut, respiratory, reproductive or skin infection, and get the bug identified through culture at a vetclinic. Sometimes you can take swabs yourself if you can work with your vet to get appropriate swabs to use. Treating blindly is sometimes all that is available to us, but if you have a chance to swab the area, your treatment will be MUCH more likely to work.

4) Get an antibiotic sensitivity test done to find what type of antibiotic works best for that bacteria.

Treating E. coli with penicillin not only will not work, it will create a whole bunch of penicillin resistant bacteria elsewhere in the body, that may become a problem later. Treat aggressively to knock back the bacterial load, and nurse the patient as best you can by keeping her warm and hydrated. Remember…..all antibiotics will do is knock back the

numbers a bit so that the hen can win the war…..if she can’t fight, your antibiotic treatment will NEVER clear the infection.

5) Use antibiotics sparingly

The more you use them, the less well they will work in the future because there will be a more resistant population of bugs around your flock due to previous treatments.

6) Do your best to clean the areas the sick birds were in contact with.

Talk to your vet and find out which bacteria like to live in the soil, or in the water, or wherever, and do your best to reduce the numbers there.

This only scratches the surface of how bacteria behave and how chickens and bacteria interact, but it will give you some basic outlines to help reduce the bacterial load in your hens.

Hope that helps!

Dr. Mike Petrik, DVM, MSc

Mike, The Chicken Vet

Thanks so much for this info from your "fantasy" vet lol. It sounds like our chickens' immune systems are fighting daily just like ours, and can get overwhelmed in similar ways, also.

So helpful to know all this!

Thanks so much for getting his help on this topic. I believe the most helpful for many will be to understand bacteria are everywhere and while yes we should take them serious, the hen can live alongside them as long as she is well kept in all manners. I believe many people may not understand many are helpful, they take up valuable real-estate keeping everything in good balance. Also, that the overuse of antibiotics causes more problems. Plus, you can't treat a nosebleed with Novocain.

I'm glad we also finally got to get his formal introduction!

You are by far my favorite chicken blogger. One thing I have always respected about you is you embrace the "natural" side of things but don't completely rely on it. You know there is a time and place for medicine and vet care. Also, you put a huge amount of research into everything you teach us about. I trust that when I read tips from you I can just implement them without having to spend a ton of time checking out the facts, you've already done that for us. The addition of Mike the Chicken Vet just makes all that… Read more »

Brilliant and well said. I want to further add that you CAN use too much DE. I was paranoid about getting mites when I first got my hens so I'd put DE in their dust bathing areas. Well, I lost two hens to inhaled the DE. Now I might put a teaspoon in their favorite spot once a year and that's it. I keep them rotating to other spots to dust bath. And I've had hens for 3 years this month and have yet to ever see a mite on a hen. So do be careful w/ the DE.

'Mike The chicken Vet' I want to THANK YOU for being willing to help Kathy get credible and attainable info to us all.

Oh it's nice to 'meet' you, :)